“There is no more love, affection and freedom behind this door.” This is how Pinho determined the time of his imprisonment in Portugal. He was six years old when he was first admitted to a correctional facility, and he went through other institutions until he managed to get out, at age 14.

Pinho, who lived between 1927 and 1993, was José Joaquim de Almeida, a Portuguese from Vila Nova de Gaia who, decades after hospitalization, became an artist and depicted his memories of the time in oil paintings and charcoal prints.

Twenty of his paintings have made it into a dossier titled “The Fate of a Boy on the Street” in the Historical Archives of the General Directorate of Reintegration and Prison Service, DGRSP, Lisbon Penitentiary, a 19th century building that collects thousands of documents about Portuguese prisons.

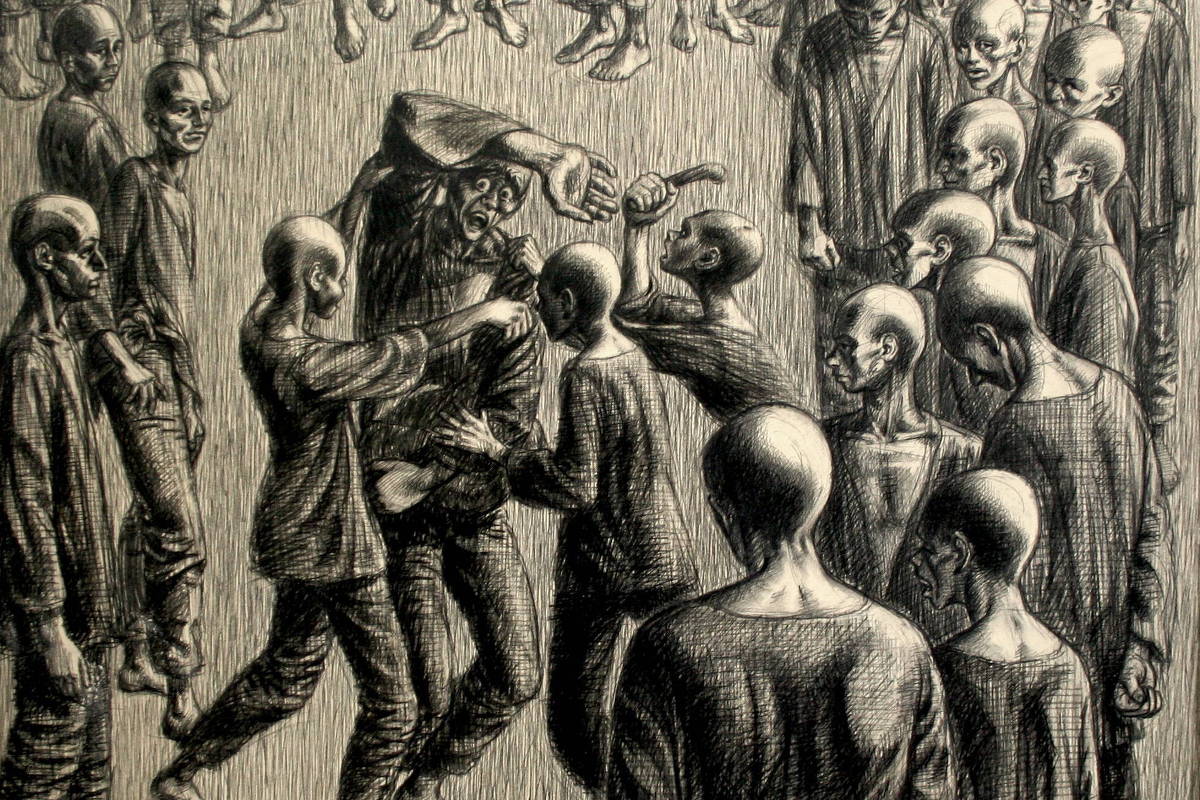

The paintings depict bars, guards, barefoot people with shaved heads and haggard bodies in blue. Looking closely, you can see that in fact these are not ordinary prisoners, adults, but children carrying crayons in their uniforms pocket.

An unsigned text was attached to the paintings. “Those who have lived their childhood within the walls are always on the run, always alone in the crowd,” says one passage.

Upon discovering the works, Brazilian historian Vivian Borges was fascinated by the brightness of the images and the mystery given the lack of information about the author. It was February 12, 2019, his first day of doctoral studies in Portugal.

“The screens seemed to be trying to tell a story, they were pointing to a revelation, an attempt to attract attention or even shock the observer,” says Borges, a professor at Santa Catarina State University, who published Pinho in November, ”Published by Manicómio in Portugal under supported by the Santa Catarina State Foundation for Research and Innovation, with free distribution to museums and universities.

“Pinho was an empathetic artist who had several monsters within him. Painting helped him not only to bring beauty into his life, but also to erase what tormented him, ”says she, a specialist in prison history.

Reformation, says the historian, was the lot of children who lived on the streets either because they were abandoned or because they got there because of social situations. Pinho was not abandoned, but hospitalized due to the condition of his mother, a young unmarried woman who was facing financial difficulties. One of the pictures shows their parting at the gate.

The boy went through institutions such as the Colégio dos Carvalhos and Tutoria de Menores in Porto and the Reformatório de Santa Clara in Vila do Conde – there is no information about his records or photographs at the time. He never met his father, but learned from letters from his mother that he was living in the United States and chose his last name, Pinho, as his artistic name.

Borges had in his hand the signature “Pinho” and the dates of the paintings, but nothing more. Archivists pulled out an email from 2014 when the paintings were cataloged at DGRSP, in which a Portuguese woman asked permission from her elderly father, Antonio Fernando, to familiarize herself with the art of Pinho, with whom she lived in a correctional facility. The visit never took place, but the email was an important clue.

The historian wrote to the author of the message and arranged a trip to the city of Porto. At the meeting, he saw a short catalog of Pinho’s paintings, which indicated the address of the studio. She wrote a letter and got a call. It was Pinho’s widow, Henriquet.

“I remember how she told me that he was a born artist. “It was addiction. He had to paint, he had to paint, ”says a researcher who visited the house where the widow had lived since the 1960s and which had a workshop in an old basement, something like a basement.

“The place remains as he left it, dona Henriqueta does not take out the brushes, paints, straw hat hanging next to the easel, and the last unfinished canvas.”

Borges is part of the Marginal Archives team, which researches and works to scientifically disseminate isolation-related collections in an effort to shed light on the experiences of forced prisoners, lepers and mental hospitals.

Within this area of research, Pinho’s paintings are considered “difficult memories,” that is, they refer to dark memories “associated with a story that a person consciously or unconsciously chooses not to remember,” he says.

However, after interviewing the artist’s family and friends, the author was able to find a happy person who commented on his traumatic childhood without any problems.

After reforming the school, Pinho received a scholarship to an art school, worked with screen printing, became a successful professional, got married and had children. In the 1980s and 1990s, he painted paintings that became part of the Portuguese prison legacy.

While living in Portugal, Borges became acquainted with the Lisbon Manicómio Gallery, dedicated to artists who worked in prisons. “I admire the idea of encouraging unknown artists whose lives have been crossed by institutional experiences,” she says, who befriended the house’s founder, Sandro Resende.

Manikomio was responsible for the graphic design of Pinho’s book and will print the title for free in Portugal. In addition to being a gallery, the house is an art studio and design agency that took off at the height of the pandemic and is set to become a radio and magazine.

The title is a direct provocation to the stigma of insanity. “This is the place where art elevates creative minds, this is a space where there is no stigma,” defines Resende, the founder of this place.