The ideologically motivated hatred is so strong that insults in the streets are becoming commonplace. However, political tensions are not limited to verbal abuse. There are acts of vandalism against spaces associated with enemies, and even murders – after shouts of “kill! kill!” a group identified with military exercises finished with the enemy.

This is not Brazil in July 2022, the month of the death of a PT municipal security guard shot dead in Foz do Iguaçu (PR) by a member of the Bolsonarist criminal police. A month after ex-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT) launched a pipe bomb in Rio de Janeiro.

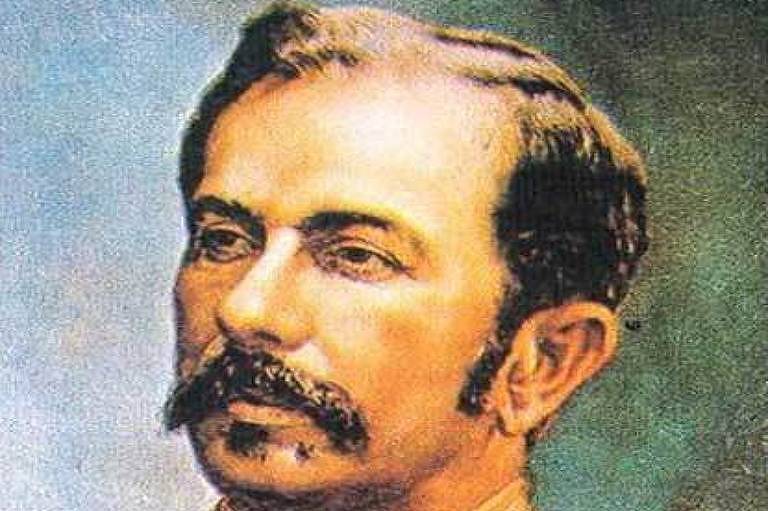

The atmosphere of terror in the first paragraph describes the conflicts on the streets of Rio in 1897. The institutional turmoil associated with violence was the result, above all, of the impulses of the Jacobins, a radical group of admirers of Floriano Peixoto, the Iron Marshal, a former president who had died two years earlier.

It is the historian Claudia Viscardi, professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora and specialist in the period known as the First Republic, who draws attention to the similarities between the behavior of the Bolsonarists today and those of the Jacobins 125 years ago. .

Brazil, of course, was very different from the country of 2022, starting with the demographics. Just over 14 million inhabitants at the time did not make up 7% of the current population. But there are also similar factors, such as violence inspired by authoritarian leaders and fueled by fabrication or overestimation of the enemy, and a strong military issue that undermines political stability.

To understand the origins of the Jacobin movement, even in general terms, it is necessary to go back a few years.

In September 1893, when Floriano was in power, the second Rise of the Armada, an uprising organized by sailors seeking more space in the new republican system. The fleet was known as the Armada, hence the name by which the rebellion became known.

In addition to supporting the army in the repressions against the sailors, the Iron Marshal actively cooperated with young people who voluntarily enrolled in the so-called “patriotic battalions”. At that time they were called Jacobins, referring to the members of the most radical political group of the French Revolution.

A distinction is worth making here: the Jacobins were Florianists, but not all Florianists were Jacobins. The latter are characterized by street agitation, often expressed by aggressiveness.

The performance of the “young patriots”, as they were also called, received more evidence from November 1894, when Prudente de Moraes, the first civilian to reach the presidency of the republic, came to power – he was preceded by Deodoro da Fonseca (from 1889 to 1891) and Floriano (from 1891 to 1894).

In order to preserve the legacy of Floriano at any cost, the Jacobins set themselves two main goals. One of them was Prudente and his supporters – at the beginning of his term, the president sought reconciliation with these more radical circles, but differences prevailed.

Another target was the restorationists who defended the monarchy, which is unacceptable for such ardent republicans.

“The restoration movement was important in some respects, but it was fragile as a political force. This threat of the return of the monarchy was much more than the alibi used by the Jacobins, as communism is used today. You have to create an enemy,” says Viscardi.

According to Amanda Muzzi Gomez, PhD in Social Cultural History at PUC-RJ, “The Jacobins portrayed the ‘monster’ of the restoration in exaggerated proportions.”

Only violence, as many of them believed, could stop this “monster”. In March 1897, the Jacobins destroyed the editorial offices and printing shops of the monarchist press in Rio and São Paulo. At that time, newspapers were mostly partisan and contributed to the buildup of political upheaval, as social networks do today.

Among the cariocas, the “Jacobin terror”, as the lawyer and diplomat Joaquim Nabuco used to say, reached a tragic level. A group of radicals assassinated Gentil de Castro, owner of newspapers that favored the restoration movement, at a railway station in Rio.

In addition to the “production of the enemy”, a strategy to keep the group cohesive and ready to attack, Claudia Viscardi points out another aspect that brings the two periods closer together. “Every time the military intervenes in politics, there is instability and the result is always violence because they have a monopoly on weapons,” he says.

Another point of contact is the leader’s fascination with the military trajectory, exacerbated by him.

There is an interesting passage in the text Jacobinism in Republican Historiography, which is part of the Political History of the Republic, a book published in 1990. glorification of Floriano, whose figure he was for them [pensamento jacobino] raised to the status of a myth.

Despite the authoritarian style, there are significant differences between the two presidents, Viscardi said.

“Floriano was more of a nationalist than Bolsonaro. In addition, he was not a loudmouth, he was more restrained,” he says. Writer Euclides da Cunha described Floriano as “avoidant, indifferent and impassive”.

The Jacobin activist Deocletian Martyr, often referring to the Iron Marshal, knew how to engage youth in conspiracy theories. One of them, Muzzi Gomez recalls, was Marcelino Bispo, a 22-year-old soldier born in Alagoas under the name Floriano.

In November 1897, under the leadership of Martyr and other Jacobin leaders, the young man carried out his plan to assassinate Prudante de Moraes. He tried to shoot the president, but his gun ran out of ammo.

In the midst of the ensuing confusion, Bispo stabbed Minister of War Carlos Machado Bittencourt four minutes later.

This was the peak of the movement’s extremism, as well as its epilogue. Radical leaders such as Martyr were arrested; Bispo was also arrested and found dead a few months later; and Prudente, on the other hand, received significant popular support.